Let me ask you something. Don’t worry, I promise I’ll talk about Pictionary in due time.

Have you ever thought about what the first modern party video game was?

I know it’s not the most important thing to ask. It’s a hard question to Google. Go ahead, try! I also know that your answer might be something obvious. In the collective pop culture zeitgeist, it’s Mario Party. As far as games that matter, it may as well be Mario Party. If you look at “List of party video games” on Wikipedia, the genre exploded after its release. You’ll also find that the answer to “first party game” was Olympic/Microsoft Decathlon. It certainly was one for MS-DOS (oy). So, why does the question even matter?

Do you know how many games are excluded from that list?

I don’t either. I do know that, in a just world, Konami’s madcap Bishi Bashi series would be an obvious inclusion. Wikipedia’s definition on that page is concise: “The genre features a collection of minigames, designed to be intuitive and easy to control, and allow for competition between many players.” Bishi Bashi games fit the bill to a tee. They also gave way to a crop of wannabes, including Namco’s Gahaha Ippatsu-Dou. Hell, Konami preceded their own trailblazer with Daisu Kiss. They preceded that with Tiny Toon Adventures: Wacky Sports Challenge. They preceded that with Track and Field.

There’s been talk about game preservation lately. Keeping digital copies of these games floating around the net is one thing. Keeping the “what”, “why” and “how” of games is another. Sure, Daisu Kiss is something you can download if you know where to find it. Language barrier aside, do you know anything about why it was made? Do you know if it was successful in the arcades? Don’t use “I’ve never heard of it” as a metric for this. In Game Machine’s October 15th, 1993 issue, two of the top five arcade games in Japan weren’t fighting games: Quiz Crayon Shin-chan and Puyo Puyo. The former was doing better. Said two games rated better than Street Fighter II Turbo. So did Data East’s Jurassic Park and Rocky & Bullwinkle pinball tables.

Wikipedia isn’t the end-all of video game knowledge. Daisu Kiss isn’t the most important game in the world. Yet, this micro-topic highlights visible holes in our collective shared memory of video games.

Party games aren’t the most substantial genre, after all.

They are mini-game collections are their core; the literal sums of their parts. They have a small reputation of being easy to crank out. Why, if you can make some mini-games… hell, if you can even provide a software element to a real-life gathering, you’ve got a shippable product. Yet, as I asked myself, “What was the first modern party game?”, I overthought how the public views video games. Not even the mainstream that has better things to do, to the chagrin of enthusiasts. Even the devotees of the Internet act aloof towards what they cannot – will not – see.

What do I define as a “modern” party game? For our purposes, I do believe Mario Party is where this genre was established as something beyond “minigames you play with your friends”. It synthesized its chaotic minigames with the experience of a board game that might be played at a real-life gathering. Mario Party could be the whole centerpiece of your party. Sessions of Track and Field and sports-based derivatives may take a few minutes if you’re good.

Board game mixed with minigames.

It’s almost too easy. Now, there have been plenty of board game adaptations on video game platforms before. There have been plenty of board games on video game platforms before. Take Anticipation for the NES, which happened to be a Nintendo first-party game by Rare. Nintendo’s first party game? Maybe not Rare’s. This was second-party developer Rare’s third party game. That is, if one wants to count the wealth of game show adaptations that exist. Oh, Rare did plenty of those. In fact, Double Dare combines trivia questions with minigames, as per typical for the show.

Anticipation is a different animal; it’s a completely original board game made for Nintendo. You pick an idiosyncratic game piece, and roll the dice to land on colored spaces in a circle. A pencil will draw something out of crude lines, and you have to buzz in a guess soon enough to get a good dice roll. It’s as if the computer is participating with you in a game of Pictionary. Wait, does that mean that Anticipation is the first modern party video game? The board game is there, but the minigames aren’t – it’s solely based around the drawing aspect.

Meanwhile, elsewhere in England, notes were being taken. Or perhaps they were given notes by a New York City-based toy company that usually took the blame for Rare’s many mistakes. With the usual deadlines, natcherally.

“Who writes this crap?”

This article is barely a review of Pictionary for the NES. It can be described in such brevity that a naked review would be pointless. However, depending on how “savvy” you are in retro gaming circles, you might already have predetermined thoughts on it. For example, it was published by LJN. It’s funny; because of James Rolfe’s Angry Video Game Nerd series, you might already think the game stinks. You might’ve had a smug overreaction of “Ah, no! I have been reminded of those egregious lords of crap,” or something else that tries to wax poetic. I bet not many people had strong, often misinformed opinions about long-defunct toy company LJN before Rolfe’s tongue-in-cheek videos came along. Not that I intend to defend their practices. If anything, they represent the long-running problem of crunch in the game industry.

Take, for example, The Karate Kid on NES. It was the second game by a fly-by-night contractor studio in Japan called Atlus. Their first was a Namco-published RPG based on a novel, titled Digital Devil Story: Megami Tensei. As we all know, Megami Tensei has done Atlus no favors whatsoever. They were also hired to do an adaptation of Jaws, but development was really headed by a studio named Westone. It happened to be that studio’s second game after a fruitless game called Wonder Boy. Other companies tapped by LJN include the unsucessful Beam Software and Sculptured Software. Lest we not forget how little good Rare and Software Creations did. Nintendo was right to never do business with them.

Wait, no, that last one doesn’t work.

If the tone wasn’t in your face enough: virtually every studio LJN tapped was reputable in some way, shape, or form. To recap: Westone’s Wonder Boy series had a complicated release history but led to some beloved action-adventures. Beam Software has a place in people’s hearts with Shadowrun. Sculptured Software made waves with their Super Star Wars series. Atlus is one of the top RPG studios today. None of these people were incompetent.

It’s also important to mention that LJN never made a game. After years of people wholly blaming LJN for rushwork, it made me realize that a publisher can usually be the target for disdain as long as their name is front and center. Consider just how many games Rare made in 1989 alone, and the grueling work ethic they embraced from the Ultimate Play the Game days all the way up to the N64’s tenure. Aside from that – if you know a thing or two about Battletoads, then you might just have to admit that some of the poor design decisions in Nightmare on Elm Street (a game that had to be rebuilt from scratch and came out 2 years after it was advertised) were a hallmark of Rare’s NES work and what came before it. Sometimes problems run deeper than company names.

We always look for something to blame when things aren’t up to code.

Perhaps with the best intentions, we want an easy boogeyman. There is some truth to LJN being a good boogeyman – Bob Gale, screenwriter of Back to the Future, had nothing nice to say about their process. A problem arises when it turns into a fascination. Why tell the story about the how, the why, and the what of a game when it’s funnier to point and laugh at a toy company that doesn’t exist anymore? Discussion about video games – discussion of all pop culture – tends to lie in brand names. This can get problematic when we’re talking about art produced with corporate money.

A universally-applicable example: executives at Paramount Global make financial decisions, while artists and writers working on SpongeBob make creative decisions. We blame “Paramount” for both when things go south. Or you do. I love sharing the storyboards that wizards like Jeff Shea, Ian Vazquez, Chris Tabares, Pinkie Davis and Eliza Herndon put out. I especially love when they explain their creative decisions. Shea once put in a tooth fairy that was made to look like she had been lifted from The Pebbles and Bam-Bam Show.

We don’t get that insight on small things often enough on video games. These bits of ephemera are prone to being lost with time and lack of care. Curiosity for said ephemera is low. This is important, because Pictionary for the NES is not a straight adaptation. It is the culmination of the place and era it was made, and the explosive gusto within. I mentioned Software Creations before, and they’re the software house of the hour today. They had a running start doing games for the ZX (zed-ex) Spectrum, one of the most popular microcomputers to hit Britain. I’ve mentioned Rare enough.

The surprise tool that will help us later is Britain.

Its gaming industry was born on the heels of the popularization of the microcomputer as a home good, once again going back to the Spectrum. It was often hopped up on the absurdist humor of Monty Python and contemporaries. Games on tape were the standard because of their cheapness. It was a wild west of unprofessional publishers and bedroom programmers who weren’t even in college yet. For our purposes, it was also common for developers to staple several smaller games together and call it a day. You see that line of thinking in certain Traveller’s Tales games such as Toy Story and Haven: Call of the King.

In this era, Software Creations had certainly found a niche with arcade conversions and whatever the hell was going on in Agent X. Like Rare, they were also a relatively early adopter of console development. Namely, NES development, which led to a fruitful first-party partnership with Nintendo when they struck gold with Solstice. By the way, Solstice’s publisher outside Europe, and the copyright holder of it and its sequel? Sony.

It took a copious amount of words to get to the video game. That’s mainly because Pictionary for the NES only makes sense with the combined contexts leading up to it. A publisher known for rushing talented people. A gaming industry that developed in a manner that seems foreign to the dominant gaming cultures of the world. Tendencies within that industry that seem outright arbitrary to anyone under the age of 40. This is 1990, and the party video game as we know it hasn’t been invented yet. Now Software Creations, a British software house, was being poked by LJN to put a drawing-based board game onto the NES.

What if they combined minigames with a larger board game?

I hardly intend to say that Pictionary is a groundbreaking experience by any means. Although it predated Mario Party by nearly a decade with its synthesis of a board game and some minigames, there’s little evidence to suggest that Nintendo or Hudson Soft had it in mind. There’s little evidence to suggest that the game sold particularly well, or if the game development community had thought anything of it. That’s entirely understandable, because Pictionary has all of the hallmarks of a rushed licensed game. It is light on content, it is repetitive, and it is visually minimalistic. It does show ambition. The gusto of the overworked British programmer is unmistakable.

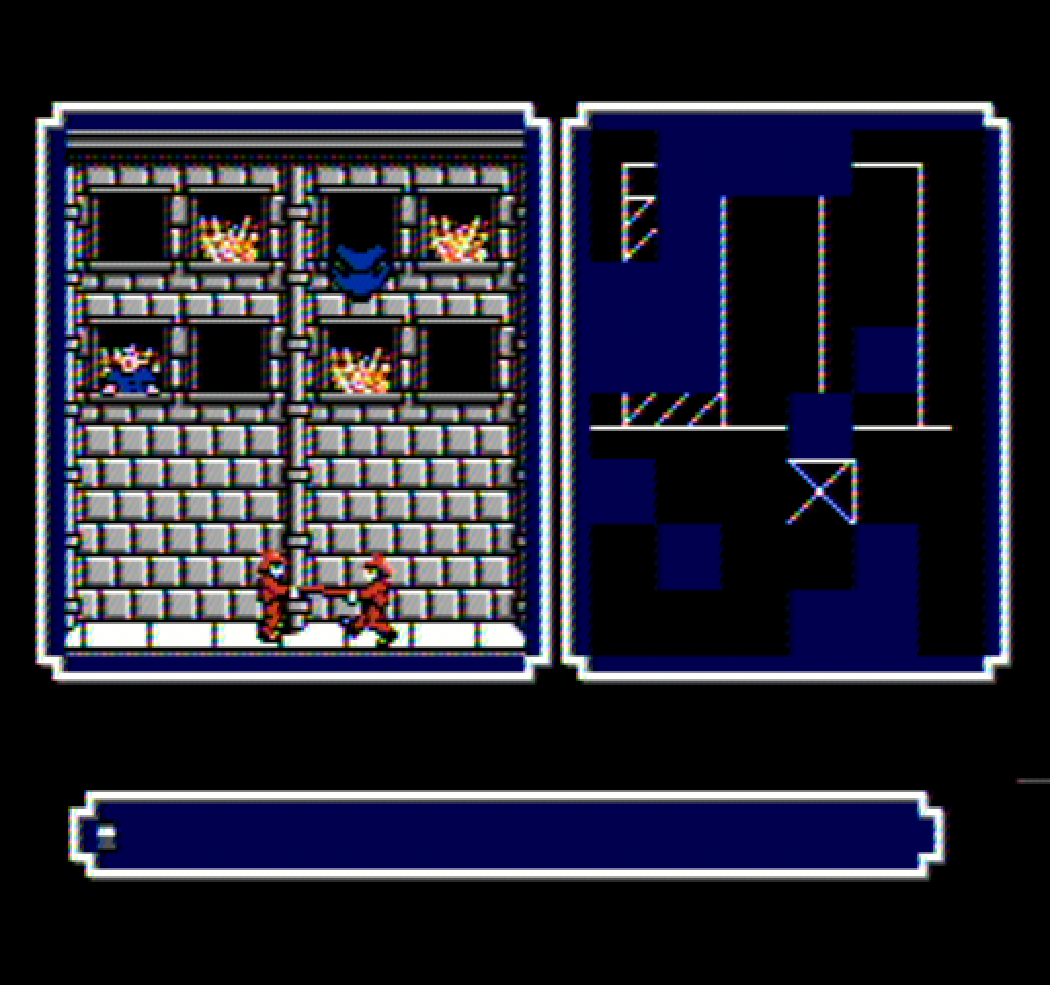

Honestly, you wouldn’t appreciate the ambition – you would hardly see any – and I don’t blame you. The board is a straight dash to the finish. You roll the dice, land on a square, and play a minigame. Some squares, in the scenario that you have teams with more than one player, will initiate a drawing game in the vein of the real-life game. If there’s only one player per team, you just play the minigames, of which there are four. For each, you have to slowly reveal the drawing by doing the designated task, and your timer is knocked off whenever you lose health. Novel enough.

Speaking of “novel”…

You already see the absurd humor through the game pieces, which are all art instruments. The minigames are something else. One is an upside-down Space Invaders where you have to drip paint on aliens – one alien equals one tile. Another is a simple platformer where you need to collect blue orbs while dodging circular pink creatures. Such creatures, although green, will also hinder your ability to carry boxes to the drawing on the right side of the screen. Finally, you have to save people from a burning building by bouncing them from a stretcher.

The instruction manual is a little funny, because it’s clearly a New Yorker trying to ground all the British surrealism. It denotes that the burning building minigame takes place in “Clonevill(e) Condos” since all the falling men look the same, and tries to rationalize the bucket of paint in the Space Invaders clone as a spaceship shaped as such. I hardly consider it “canon” to what the uncredited Software Creations people were thinking, but this is the kind of writing you lose as time erodes the gaming industry.

It’s strangely clever in its programming, even.

These minigames, in of themselves, are an early experiment in two-screen interactivity. The playfield is tiny, since the other half is the drawing you’re meant to guess. The minigames are just the right size and scope for this to work, in theory. Sadly, only two of the minigames are that fun. The burning building game is an example of unfairness by design. To be fair, given the rushed nature of the game, I have an idea of what problem it was trying to solve: the timer runs at a glacial pace. By having two guys fall at the same time, or so close that your slow little firemen can’t reach in time, you don’t risk the minigame ruining the pacing of the entire experience. Unfortunately, it’s a half-baked solution: a lot of the tiles that you can get are completely blank, and the drawings are made of crude lines.

Now, the drawings being made of only a few stored tiles is a genius space-saver, but when you can’t be good enough at the minigame to guess what something even is, you’re going to be forfeiting your turns often. As for the box minigame, it’s also much too difficult to help the game’s end goal, thanks to the speed of the enemies. As for the experience of going through the minigames, forfeiting turns until someone gets something means that you’re going to end up seeing the same minigames be played over and over.

And that was the review.

Besides an alternate mode where someone can use their existing Pictionary set to play, that’s it for Pictionary on NES as a video game that I can sufficiently review. It is experimentation in the face of grueling capitalism, and the latter had won from the start. Pictionary tries to be something unique for a board game adaptation, a point that LJN boasts in the game’s instruction manual. The devs took various steps to fit the act of putting together various drawings with a tiny repertoire of sprites, alongside half of the screen being dedicated to a functional game. It has to do so in the face of the NES’ horizontal sprite limit (it is a miracle that any of the minigames run as smoothly as they do).

All the things you have to consider for a game of this type are hard enough to implement in a modern engine. These guys had to do that in assembly for a console that was superseded a few times over by other machines (the Sega Mega Drive dropped in the UK the same year as this, the Amiga was out for five years).

The Non-Existent Credits Roll

It’s all so impressive that, if the hidden staff list in the code is anything to go by, only three people worked on this. Granted, that’s an average size for a ZX Spectrum budget release (natch). I just know LJN charged $50 or more for this, though – now that I think about it, MSRPs are something we also lose with time. Oh, to know the stories of everyone who worked on this.

The sole programmer was Tony Pomfret, who presumably started at Ocean Software working on Daley Thompson’s Decathlon. The graphics were done by Craig Houston, who somehow has the wildest resume of the three. He either shares a name with, or is, the former lead writer for the Call of Duty series. If that’s true, you’d think it’d be the biggest name that people associate with Pictionary. He would be the biggest name overall, but people don’t associate Pictionary with him.

The musician of this game is Tim Follin.

That is a man who people are weird about.

And I can’t say I don’t get it, to an extent. For those not in the know, Tim Follin is one of three brothers who worked at Software Creations. He was a sound guy who could program. Michael Follin usually did programming – he is now a Reverend. Geoff was the other staff musician, and often collaborated with Tim. Not that you’d know that – sometimes, people only care about Tim. For all it’s worth, Tim Follin is talented.

Before he turned 18, he wrought complex music from a computer with no sound chip (it sounded like angry wasps, and I fuck with it). That kind of gusto – not only of a busy British programmer, but of a zealous youth – went into everything he composed. Upon being tasked with porting the music of Capcom classics such as Ghouls ‘n’ Ghosts and Bionic Commando, he decided that it was his to transform into something completely different.

It was during this period of pure gusto that Tim adorned Pictionary with a prog rock soundtrack. Tim admits that he hardly paid attention to what game he was composing for during the NES period – once again, zealous youth. He actually wasn’t too proud of his early work when asked later, although further retrospective interviews have seen him be kinder to it. He was so over chip music when he had the opportunity to work on Ultraverse Prime for the Sega CD.

In any case, Tim Follin has been historically humble about his work.

Audience response to it is the opposite.

![Tumblr conversation. "unregistered-hypercam2" makes two posts.

(1)

nintendo: hey tim we're making a dumb pictionary game and need some music

tim follin: >:)

(2)

nintendo guy calling tim follin: hey bud, have you... have you ever played pictionary?

followed by a final post by "get-thee-to-a-shrubbery".

Nintendo guy: so we're making a game that, honestly, probably won't sell well, who wants to do the music?

Tim Follin, vaulting over chairs and tables: DIBS FUCKING DUBS [gag, hack]](https://beatvidalia.net/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/firefox_3cdwbtuyf6.png?w=614)

Many screenshots can demonstrate millennial Tumblr to a winceworthy degree, but this is up there for me. This is the kind of characterization you’d see dredged up on “heritageposts,” a now-inactive account that resurfaces embarrassing fandom posts from the early 2010s. This was firmly in the era that Tumblr users were heads over heels for Doctor Who, and even going as far as to blindly and fetishistically give reverence to British culture. I’m not even sure if anyone involved in this exchange knew that Tim Follin was British, but it fits snugly among the squeeing Benedict Cumberbath fangirls.

Okay, so what’s really the problem?

Tim Follin deserves praise for his work. The fashion in which people assign praise to him is corny at the not-so-best of times, and teeters onto misinformation at the worst of times. I have to discuss Plok in this regard, itself made fun of as a hallmark of “weird, failed mascot platformers.” Really, it was one of the Software Creations titles blessed with immense creative control, and was inches away from being Nintendo IP. People will pass around the rumor that Shigeru Miyamoto listened to the music and thought that it was streamed audio. There was no source for this for years, but people bought it. Said source has been discovered – this was smack dab in the middle of SC’s Nintendo partnership – and it turns out that it was something of a game of telephone between Miyamoto and Nintendo of America alumni Tony Harmon.

People will also tend to accredit Plok’s amazing soundtrack to Tim, despite Geoff Follin being co-credited; co-creator Ste Pickford recalls Geoff doing a lot of the work. “Tim was a bit more… elusive,” he says, albeit establishing that Tim was probably responsible for the more famous bits of the sound. And yet, it’s so common to see Tim characterized as an excitable god of video game music who loved doing funny little tunes for the “Nintendo guy.”

I don’t expect people to become hyperfixated retro game scholars.

It does hurt to see a lack in people’s curiosities for video games of times past. “The past,” from the dawn of mankind to the roaring twenties to the blur of twenty-twenty, can all be viewed from a standstill as one misrepresented mush. A lot of the recorded history people care about is firmly within their own country or whatever other country they fetishize. Anything else is treated as a curiosity, laden with urban legends, mistruths, and racist rhetoric at worst. Even in our current time, people still whine about “anime bullshit” (whatever that means) invading their quarterly Nintendo commercial compilations, and that’s keeping in mind that Japan is one of the “cool” video game countries.

When you listen to Tim Follin’s music, when you play any game to originate from the United Kingdom – any European country, even – do you ever think about everything that might’ve led up to it? Follin was barely alone in the culture of wringing every note from a primitive computer chip. Jeroen Tel, Alberto J. Gonzalez, Martin Galway, Jonathan Dunn, Rob Hubbard, Matt Furniss, Dean Evans, and Chris Huelsbeck were/are just a few of the exceptional composers for retro video games in the UK and beyond. You still hear arp-filled European chiptunes when you pirate a video game – it’s the soundtrack that powered the demoscene, which itself fed back into the gaming industry.

Why stop there?

Not that video game history lacks oddities altogether, but how many people can you say are retelling the stories of lesser-known video game cultures on a worldwide scale? Without any smug reimaginings. I’m guilty of feeling bitter towards the sphere of old computer games from Europe (particularly the UK), but mainly because I came to despise myself for wanting to learn. People need to know about the time when children had to load games off of a cassette tape, even if it wasn’t in good ol’ ‘Murica.

They need to know about the place where sprawling exploration platformers with a smug cruelty were the talk of the town, before others had further innovated with Metroid. Is Lenslok not a valuable lesson in shoddy copyright guarding? One of the games cursed by it is Elite, an early experiment in 3D gaming. Incidentally, the first video game that came packaged with a full novella. Most of these are pretty big things to learn about, and many people simply don’t. Here I am worrying about people not giving an ass’s ass about much less significant things in their hobby.

Pictionary for NES kind of stinks, but not without trying.

Really, it’s the perfect storm of demonstrating the gaps of ignorance that could pop up for any other video game. Just the logo on the front is enough to flare up biases based on farce. The developer not on the box was just one of many to be crunched – but clearly, they were incompetent. And why did the composer who I think may or may not be a real-life Goku do their job for the drawing game? These rock tunes really don’t fit the hectic, absurdist minigames. It’s an old game, of course it sucks. It’s Bri’ish, of course it’s a weird game.

Video games, being the interactive medium that they are, essentially allow people to confront the decisions someone behind the scenes has made. If the “right” decision to get the game shipped happens to be the wrong one, one may feel like they’re being actively spited. This phenomenon also happens for non-interactive media – see how people react to SpongeBob episodes in which the crew spitball their gleeful in-jokes, or whenever The Simpsons shifts the timeline up for an episode to score a neat story opportunity. The effect is multiplied when you have to deal with the decision yourself. Suddenly, and with the multiplier of a geological and temporal divide, you want to call the boogeyman a slur.

So back to my dumb question.

“What is the first modern party video game?”

It might be Pictionary. It might as well be Mario Party. I am willing to surrender that answer. What I’m not willing to do is surrender the thought that people won’t ask questions about the games that came before theirs. I don’t care if it came from a country or era that they’re not wholly familiar with. As a matter of fact, I don’t care if it’s wonky to play, or even if it features values that plain sucked then and suck now. I want people to ask questions about video games with more empathy and more curiosity. I want them to think about “how,” “when,” “what,” and “why.” Then, I want them to learn, even if it’s just a little. Even if it’s just “I didn’t know that computer existed, the more ya know.”

I want the general public to question the urban legends they may have picked up on Twitter some eons ago. They might also benefit to think before dismissing some old, never-ever-gonna-come-back game being thrown back into the ether. I want bad games, totally unimportant games, to be preserved. A lot of the preservation issue lies with copyright law and corporate greed. A chunk of it lies with how we approach this topic.

We might get somewhere better with video game preservation if people asked good questions about a crappy little game like Pictionary.

Leave a Reply